The Curious Case of Well-Behaved Matrices

A few days ago, a friend of mine suggested using "low-rank methods" in my neural networks from-scratch work to showcase how basic concepts of linear algebra play an important role in neural networks. I started digging into the topic, and while surfing the internet, I stumbled upon this comment on Reddit saying, "initialize your weights orthogonally for better stable gradients".

The idea of orthogonally initialized weights is fascinating, but I couldn't find any good explanation stating why this method works, so I decided to cook up some math myself.

1. Understanding gradients

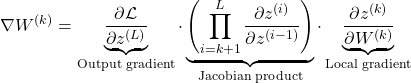

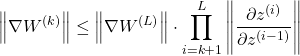

To understand how orthogonal initialization helps, I started analyzing the gradient matrix. I wrote the gradient equation and broke it into three major parts like this:

This scary-looking expression is nothing but a chain of matrix products, which helps in visualizing how gradients flow in neural networks:

- The first term is the gradient of the loss with respect to the output of the last layer.

- The middle term forms a sequence of Jacobian matrices, each representing how the output of one layer depends on the previous.

- The last term is the local gradient, i.e., how the output of layer ( l ) depends on its own weights.

What matters here is the middle product of Jacobians because it carries the gradient signal backward through the layers.

2. Analyzing jacobians

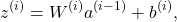

Considering a linear layer like this:

Its Jacobian will be written as:

Again, a scary-looking equation, but it's just simple calculus.

Key observations from this equation:

- If I use ReLU as my activation, then the derivative of it will be either 0 or 1.

- The Jacobian matrix is directly dependent on the weight matrix.

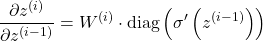

Thus, the product of Jacobian matrices in the first equation can be replaced by:

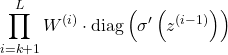

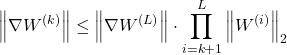

3. Expressing gradient equation using matrix norms

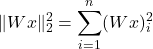

Using the submultiplicative property of matrix norms on the gradient equation:

From the earlier equation, I rewrote the gradient equation by replacing the Jacobian matrix with the weight matrix like this:

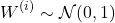

4. Case 1: Gaussian initialization of weights

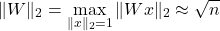

If I initialize weights with entries drawn i.i.d. from a normal distribution:

Then the spectral norm of the weight matrix will be:

This is because:

- The output of multiplying a vector with Gaussian ( W ) is just a weighted sum of n Gaussian columns.

- Each component in such a product will be a Gaussian with variance 1.

- Thus, the squared norm will be the expected value of a Gaussian, i.e., n.

And thus we get:

In the equation from Expressing Gradient Equation Using Matrix Norms, the spectral norm of the weight matrix will be replaced like this:

This will grow exponentially for ( n > 1 ) and will vanish quickly for ( n < 1 ), and thus in turn affect the value of the gradient (as we proved earlier, gradient values directly depend upon the weight matrix).

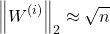

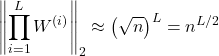

5. Case 2: Orthogonal initialization

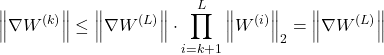

If we initialize weights orthogonally by using QR decomposition on weights sampled from a normal distribution, then we know that their singular values will be 1 because:

And thus, I can substitute this in the original gradient norm equations, resulting in:

As you can see, the gradients are stable and won’t explode or vanish even if we have huge depth in our neural network.

Thank god, the math works out

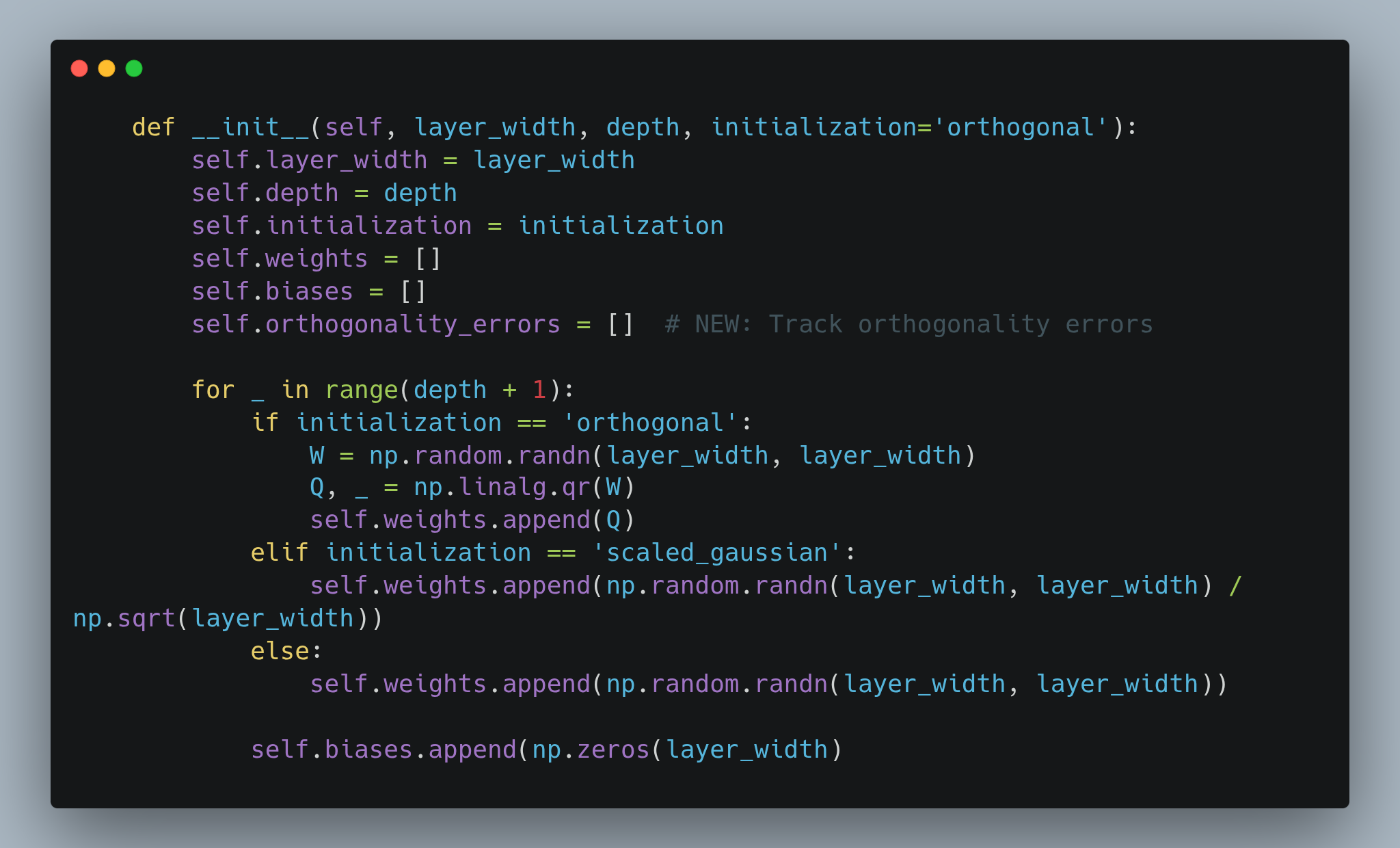

I modified my code from the last blog by increasing layers and their widths and initializing weights orthogonally using QR decomposition.

And it turns out that all this math I did till now works out (thank God!).

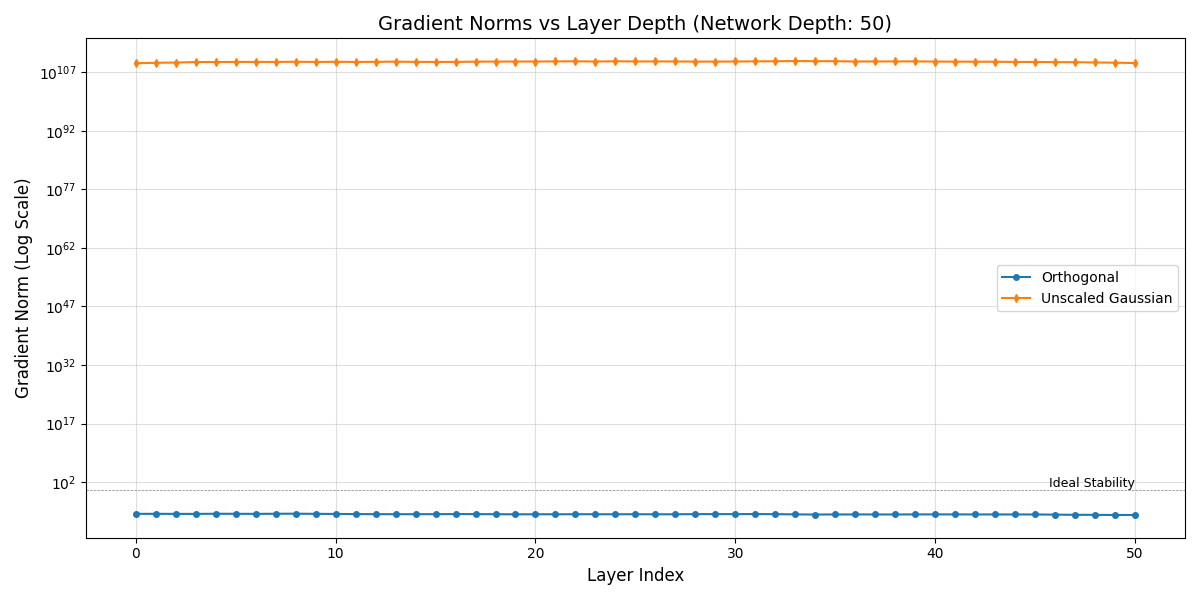

I plotted the gradient norms vs. layer depth for Gaussian weights and orthogonal weights.

Clearly, for Gaussian-initialized weights, the norms of gradients explode, while for orthogonally-initialized weights, the gradient norms stay within a good range.

(I generated synthetic data using np.rand for this.)

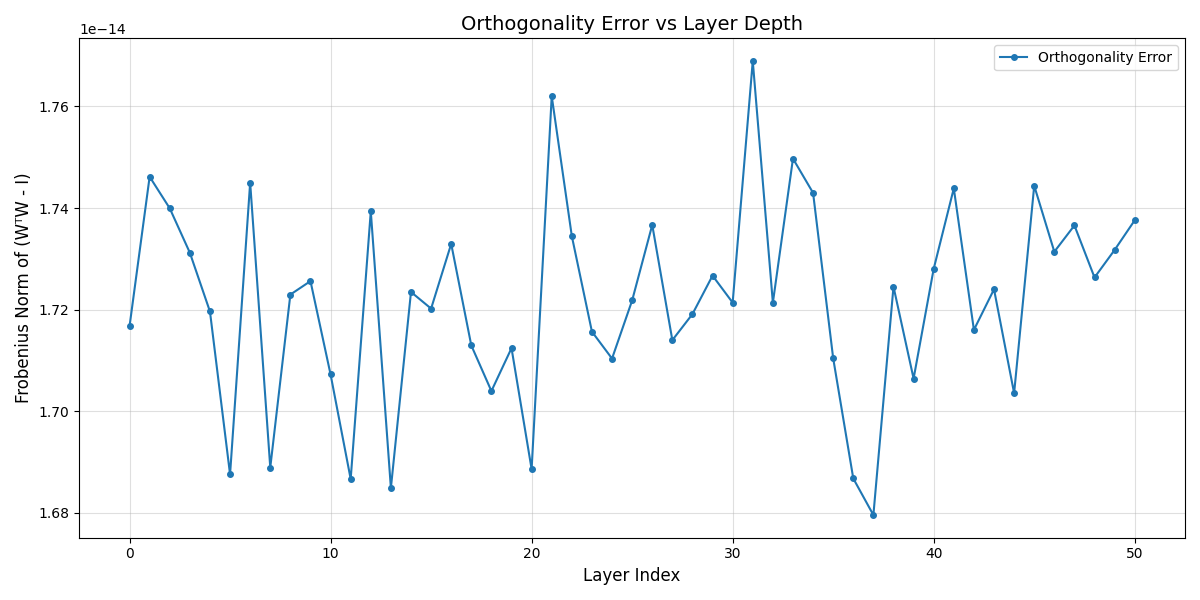

But how are the weights orthogonal throughout the training process???

I tried to verify if the weights are orthogonal or nearly orthogonal by tracking them during backpropagation:

Even after working out the math and implementing everything, I still can’t understand how the weights remain orthogonal or nearly orthogonal.

Maybe a good topic for the next blog.

Hope you got some good insights from this!